Exhibition of art without borders comes to Miami's Dade College

In melting-pot Miami, group show focuses on work with themes of immigration and identity

The Carribean poet and cultural theorist Édouard Glissant claimed his right to opacity at a 1969 congress for the National Autonomous University of Mexico. “There’s a basic injustice in the worldwide spread of the transparency and the projection of Western thought,” he told the audience. “Why must we evaluate people on the scale of the transparency of ideas proposed by the West?”

That question underwrites much of Where the Oceans Meet, an exhibition at Miami Dade College Museum of Art and Design that analyses the follies of border mentality. The show lists Glissant as a major influence alongside Lydia Cabrera, the Cuban painter and ethnographic scholar who became a stalwart of the Afrocubanismo movement.

“The beauty of this exhibition is its curation of thinkers,” says the museum’s executive director and chief curator Rina Carvajal, who organised the show together with Hans Ulrich Obrist from London’s Serpentine Galleries, Gabriela Rangel from the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires, and the artist Asad Raza. “Artists are speaking about immigration policies, memory, identity, displacement, war, capitalism and religion. It’s about finding a way to connect with other people while respecting our differences,” Carvajal says.

The show is dedicated to the renowned Nigeran curator Okwui Enwezor, who died of cancer during the show’s preparations in March. “He was a pioneer of this notion of crossing borders and connecting continents,” Carvajal says. “The dedication felt important for all of us who worked with Okwui over the years.”

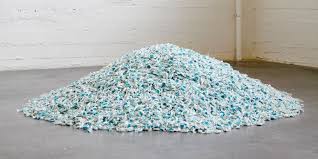

Accordingly, it casts a wide net around the world, gathering artists as disparate as Tania Bruguera and Walid Raad, Félix González-Torres and Yto Barrada, Glenn Ligon and Jack Whitten. Together, they celebrate the intellectual curiosity and political gumption of Cabrera, who disrupted racial barriers by elevating Afro-Cuban culture without prejudice for social and economic class hierarchies.

A highlight is Lani Maestro’s A Book Thick of Ocean (1993)—a tribute to the Filipino-Canadian artist’s “Nanay” or “heart mother”. Within its 500 pages are notions of repetition and longing—potent themes for Maestro, who went into political exile in Canada after demonstrating against the Philippines’s repressive regime in 1982. Consequently, the exhibition aims to push ideological boundaries between different modes of personhood and cultural placemaking.

“Global exchanges have always been so important,” Asad Raza told the Miami New Times. “They’re not new, and the neo-nationalist ideas that are in the air these days that claim we can reject the ‘other’ and foreign influences and return to an imaginary purity are complete nonsense. But too often the artificial, sterile globalisation process homogenises culture. Instead, we need to exchange with each other the way Cabrera and Glissant demonstrate and create a much richer and more diverse cultural soil.”

As a melting pot of its own for American and Caribbean cultures, Miami is a fitting stage for this type of show, where visitors are asked to question concepts of authority, identity and terrain. Around half of the city’s residents are foreign-born, with Miami Dade College boasting more than 197 nationalities among its student body, according to Carvajal.

“This exhibition is delicately woven,” she adds. “Miami is full of immigrants—we are already a very diasporic community.”