- Details

- Written by Polina

- Category: Modern paintings

- Hits: 1126

Fresh meat: painting restoration reveals that hunk of beef thought to be cooked was actually raw

The 17th-century work features in a newly opened exhibition on art and food at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge

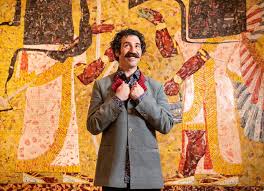

A mighty feast of roast beef ready for the table has been transformed into a glistening slab of raw meat, to the surprise of the conservators who cleaned a 400-year-old painting for an exhibition on food opening today at the Fitzwilliam Museum in Cambridge.

The view of heaped ingredients and gleaming pots and pans was made in around 1620 by the Dutch artist Floris Gerritsz van Schooten, who is renowned for his kitchen still life paintings. The work, which has been in the Fitzwilliam collection for 200 years, had a coat of discoloured varnish that appeared to show grimy utensils and a rather sooty roast sirloin with a thick layer of yellowed fat.

The conservation work, which was undertaken by Victoria Sutcliffe at the university's Hamilton Kerr Institute laboratory, shows that the shining copper and brass pans are a credit to the kitchen workers, and the pink beef is still raw, awaiting the cook's attention.

Sutcliffe's work has also revealed details that were previously barely discernible, including the scars on the lower legs of the rabbits from the snares used to trap them, and Van Schooten's initials on the stone ledge under the produce. And her work showed that the back of the canvas is a rare example of a 17th century work that escaped later re-lining, a technique to strengthen the work but which can have the effect of flattening the paint surface.

Victoria Avery, the keeper of applied arts at the Fitzwilliam and the joint curator of the exhibition, commented that the heap of autumn ingredients including fish and meat, pumpkins, cabbage and peas, also documents the range of produce available in 17th-century Haarlem, and the cooking methods used, while the well scrubbed pots testify to more than just the hard work of the kitchen staff. “All of them have sparkling insides but only some of them have shiny outsides, which reveals that they were used for different kinds of cooking over different kinds of fuel," she says. "Those pots with shiny outsides must have been used for making preserves or other food that required precise temperature control over charcoal. While the blackened pots were for cooking meat or vegetables over an open wood fire, she explained: “Burning charcoal releases carbon monoxide that reduces any oxides or other stains on copper leaving a pan’s surface remarkably clean and shiny.”

The exhibition brings together rare loans from Cambridge colleges and libraries, and private and museum collections across Cambridgeshire and beyond. Recreated feasts include a banquet of sugar sculptures fit for a Renaissance wedding made by the food historian Ivan Day. A giant pineapple, by artists Bompass and Parr, has also sprouted on the lawn outside the museum.

The Van Schooten is among many works released from decades in museum stores and specially conserved for the exhibition. Avery thinks its restoration is a revelation. “Even the best photography doesn't do it justice, as it's on such a large scale, and we've deliberately hung it low for children and wheel-chair users, so everyone can really appreciate the brilliant brushwork and painterly illusionism” she said.

- Details

- Written by Polina

- Category: Modern paintings

- Hits: 1037

Three exhibitions to see in London this weekend

From the UK's hottest graduates to forgotten Indian masterpieces

Group shows of graduating, or recently graduated, artists are invariably a mixed bag: a cross section of what is spilling out of art schools now, with larger patterns often only discernible many years later. But several themes definitely crop up in this year’s Bloomberg New Contemporaries exhibition, which opens today at the South London Gallery (until 23 February 2020; free). The rise and rise of gestural, naïve painting is still going strong, as is a fun DIY ethos when making video works. There are some more serious themes explored with works about marginalised communities and touch of recent politics too—Boris Johnson and Grenfell are subjects of paintings—but on the whole, this is a playful bunch. There are examples of humour throughout, from subtle titling, such Jan Agha’s portrait Pompous Prick (2019), to a deadpan collection of 91 slightly different shades of blue postcard in Paul Jex’s Yves Klein IKB 79 or Tate Modern keeps getting it wrong (2016). The video works—which thankfully for a group show are mostly short—often embody the absurd, whether it is Annie Mackinnon’s Compost Daddy (2018), where her father wears a plastic suit filled with manure to poke fun at the fashion industry; Taylor Jack Smith’s sobbing cartoon man in Bawler (2018); or the moment when SpongeBob SquarePants has his nose pulled off by one of the teenage dancers in Roland Carline’s video. There seems also to be an appreciation of the formal qualities of works, such as in Camille Yvert’s movable polystyrene sculpture Permanent Transit (2018) or Renie Masters’s cut-out sculptures A Hard Rock to Carry (2018). The exhibition, with a dozen fewer artists than last year, seems breezier than usual and is perhaps also a reflection of the strong selection panel—the artists Rana Begum, Sonia Boyce and Ben Rivers—as much as what art schools are rolling out.

Peggy Guggenheim and London at Ordovas (until 14 December; free) takes place around the corner from where the American heiress ran a short-lived gallery in a former pawnbrokers on Cork Street on the eve of the Second World War. The show illuminates Guggenheim Jeune’s attempt to stir an avant-garde scene in London, with facsimiles of private view invites for shows mixing the latest Parisian tendencies with an emerging stable of British artists. (Marcel Duchamp, no less, served as the gallery’s primary curatorial advisor.) An elegant hang plays on the biomorphic affinities between two key artists: the sculptor Hans Arp, from whom Peggy Guggenheim made her first art acquisition in 1937, and the painter Yves Tanguy, whose 11-day solo show in June 1938 closed the gallery’s first season on a critical and commercial high. Museum-quality loans from private collections and, indeed, the Hepworth Wakefield and the National Galleries of Scotland, evoke the dialogue between abstraction and surrealism that would come to characterise Guggenheim’s own collection—a fascinating foretaste of the house-museum that still bears her name on Venice’s Grand Canal today.

How many Indian naturalist painters of the 19th century can you name? Chances are extremely few, more likely none at all. Works from this period are some of the finest animal and botanical works in the world. Yet for centuries the indigenous artists behind these depictions of animals, plants and village life have been relegated to nameless artisans from local schools, with the focus directed at the European East India Company officials who commissioned them. Undertaking the important task of righting this historic wrong, the Wallace Collection has brought together more than 100 watercolour-on-paper works for Forgotten Masters (until 16 April 2020; tickets £13.50, concessions available) and the results are magnificent. Here the sleekness of a Sambar deer's fur is expertly captured by the Muslim painter Shaikh Zain Ud-Din, who was so skilled he could accurately convey the movement of water through the trailing spines of a mango fish, even though it is painted on a blank background. The botanical works on show are especially strong—the tangential tendrils of a cobra lily by Vishnupersaud are more playful than anything his Western peers were producing. Throughout these works the client's brief—to create accurate scientific studies— is tempered by Mughal-influences. Where people appear, they are mainly villagers and courtiers (the curator William Dalrymple tells The Art Newspaper that these are some of the earliest recordings of Indian villagers with identifiable faces). Depictions of Westerners often hint to underlying tensions between artist and patron, such as a (presumably) white child on horseback whose entire face is obscured by her hat. Although the show could go further in addressing the social reality of the East India Company, it does recognise the thorny colonial context of these paintings that explains why these artists have been ignored by Western institutions for so long. This is a move that will no doubt help to reposition the Wallace Collection as a forward-thinking institution that is willing to play a part in rebalancing the canon.

- Details

- Written by Polina

- Category: Modern paintings

- Hits: 1272

Why art has the power to change the world

One of the great challenges today is that we often feel untouched by the problems of others and by global issues like climate change, even when we could easily do something to help. We do not feel strongly enough that we are part of a global community, part of a larger we. Giving people access to data most often leaves them feeling overwhelmed and disconnected, not empowered and poised for action. This is where art can make a difference. Art does not show people what to do, yet engaging with a good work of art can connect you to your senses, body, and mind. It can make the world felt. And this felt feeling may spur thinking, engagement, and even action.

As an artist I have travelled to many countries around the world over the past 20 years. On one day I may stand in front of an audience of global leaders or exchange thoughts with a foreign minister and discuss the construction of an artwork or exhibition with local craftsmen the next. Working as an artist has brought me into contact with a wealth of outlooks on the world and introduced me to a vast range of truly differing perceptions, felt ideas, and knowledge. Being able to take part in these local and global exchanges has profoundly affected the artworks that I make, driving me to create art that I hope touches people everywhere.

Most of us know the feeling of being moved by a work of art, whether it is a song, a play, a poem, a novel, a painting, or a spatio-temporal experiment. When we are touched, we are moved; we are transported to a new place that is, nevertheless, strongly rooted in a physical experience, in our bodies. We become aware of a feeling that may not be unfamiliar to us but which we did not actively focus on before. This transformative experience is what art is constantly seeking.

I believe that one of the major responsibilities of artists – and the idea that artists have responsibilities may come as a surprise to some – is to help people not only get to know and understand something with their minds but also to feel it emotionally and physically. By doing this, art can mitigate the numbing effect created by the glut of information we are faced with today, and motivate people to turn thinking into doing.

Engaging with art is not simply a solitary event. The arts and culture represent one of the few areas in our society where people can come together to share an experience even if they see the world in radically different ways. The important thing is not that we agree about the experience that we share, but that we consider it worthwhile sharing an experience at all. In art and other forms of cultural expression, disagreement is accepted and embraced as an essential ingredient. In this sense, the community created by arts and culture is potentially a great source of inspiration for politicians and activists who work to transcend the polarising populism and stigmatisation of other people, positions, and worldviews that is sadly so endemic in public discourse today.

Art also encourages us to cherish intuition, uncertainty, and creativity and to search constantly for new ideas; artists aim to break rules and find unorthodox ways of approaching contemporary issues. My friend Ai Weiwei, for example, the great Chinese artist, is currently making a temporary studio on the island of Lesbos to draw attention to the plight of the millions of migrants trying to enter Europe right now and also to create a point of contact that takes us beyond an us-and-them mentality to a broader idea of what constitutes we. This is one way that art can engage with the world to change the world.

Little Sun, a solar energy project and social business that I set up in 2012 with engineer Frederik Ottesen, is another example of what I believe art can do. Light is so incredibly important to me, and many of my works use light as their primary material. The immaterial qualities of light shape life. Light is life. This is why we started Little Sun.

On a practical level, we work to promote solar energy for all – Little Sun responds to the need to develop sustainable, renewable energy by producing and distributing affordable solar-powered lamps and mobile chargers, focusing especially on reaching regions of the world that do not have consistent access to an electrical grid. At the same time, Little Sun is also about making people feel connected to the lives of others in places that are far away geographically. For those who pick up a Little Sun solar lamp, hold it in their hands, and use it to light their evening, the lamp communicates a feeling of having resources and of being powerful. With Little Sun you tap into the energy of the sun to power up with solar energy. It takes something that belongs to all of us – the sun – and makes it available to each of us. This feeling of having personal power is something we can all identify with. Little Sun creates a community based around this feeling that spans the globe.

I am convinced that by bringing us together to share and discuss, a work of art can make us more tolerant of difference and of one another. The encounter with art – and with others over art – can help us identify with one another, expand our notions of we, and show us that individual engagement in the world has actual consequences. That’s why I hope that in the future, art will be invited to take part in discussions of social, political, and ecological issues even more than it is currently and that artists will be included when leaders at all levels, from the local to the global, consider solutions to the challenges that face us in the world today.

- Details

- Written by Polina

- Category: Modern paintings

- Hits: 1017

Exhibition of art without borders comes to Miami's Dade College

In melting-pot Miami, group show focuses on work with themes of immigration and identity

The Carribean poet and cultural theorist Édouard Glissant claimed his right to opacity at a 1969 congress for the National Autonomous University of Mexico. “There’s a basic injustice in the worldwide spread of the transparency and the projection of Western thought,” he told the audience. “Why must we evaluate people on the scale of the transparency of ideas proposed by the West?”

That question underwrites much of Where the Oceans Meet, an exhibition at Miami Dade College Museum of Art and Design that analyses the follies of border mentality. The show lists Glissant as a major influence alongside Lydia Cabrera, the Cuban painter and ethnographic scholar who became a stalwart of the Afrocubanismo movement.

“The beauty of this exhibition is its curation of thinkers,” says the museum’s executive director and chief curator Rina Carvajal, who organised the show together with Hans Ulrich Obrist from London’s Serpentine Galleries, Gabriela Rangel from the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires, and the artist Asad Raza. “Artists are speaking about immigration policies, memory, identity, displacement, war, capitalism and religion. It’s about finding a way to connect with other people while respecting our differences,” Carvajal says.

The show is dedicated to the renowned Nigeran curator Okwui Enwezor, who died of cancer during the show’s preparations in March. “He was a pioneer of this notion of crossing borders and connecting continents,” Carvajal says. “The dedication felt important for all of us who worked with Okwui over the years.”

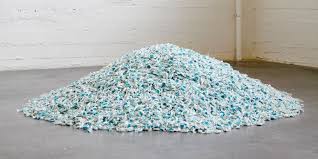

Accordingly, it casts a wide net around the world, gathering artists as disparate as Tania Bruguera and Walid Raad, Félix González-Torres and Yto Barrada, Glenn Ligon and Jack Whitten. Together, they celebrate the intellectual curiosity and political gumption of Cabrera, who disrupted racial barriers by elevating Afro-Cuban culture without prejudice for social and economic class hierarchies.

A highlight is Lani Maestro’s A Book Thick of Ocean (1993)—a tribute to the Filipino-Canadian artist’s “Nanay” or “heart mother”. Within its 500 pages are notions of repetition and longing—potent themes for Maestro, who went into political exile in Canada after demonstrating against the Philippines’s repressive regime in 1982. Consequently, the exhibition aims to push ideological boundaries between different modes of personhood and cultural placemaking.

“Global exchanges have always been so important,” Asad Raza told the Miami New Times. “They’re not new, and the neo-nationalist ideas that are in the air these days that claim we can reject the ‘other’ and foreign influences and return to an imaginary purity are complete nonsense. But too often the artificial, sterile globalisation process homogenises culture. Instead, we need to exchange with each other the way Cabrera and Glissant demonstrate and create a much richer and more diverse cultural soil.”

As a melting pot of its own for American and Caribbean cultures, Miami is a fitting stage for this type of show, where visitors are asked to question concepts of authority, identity and terrain. Around half of the city’s residents are foreign-born, with Miami Dade College boasting more than 197 nationalities among its student body, according to Carvajal.

“This exhibition is delicately woven,” she adds. “Miami is full of immigrants—we are already a very diasporic community.”